“On a gathering storm comes

a tall handsome man

In a dusty black coat with

a red right hand…”

Warm up with some evil via Nick Cave and the Bad Seed’s ‘Red Right Hand’.

and now to bring it all to a close:

Hearts of Darkness Assessment 2016

“On a gathering storm comes

a tall handsome man

In a dusty black coat with

a red right hand…”

Warm up with some evil via Nick Cave and the Bad Seed’s ‘Red Right Hand’.

and now to bring it all to a close:

Hearts of Darkness Assessment 2016

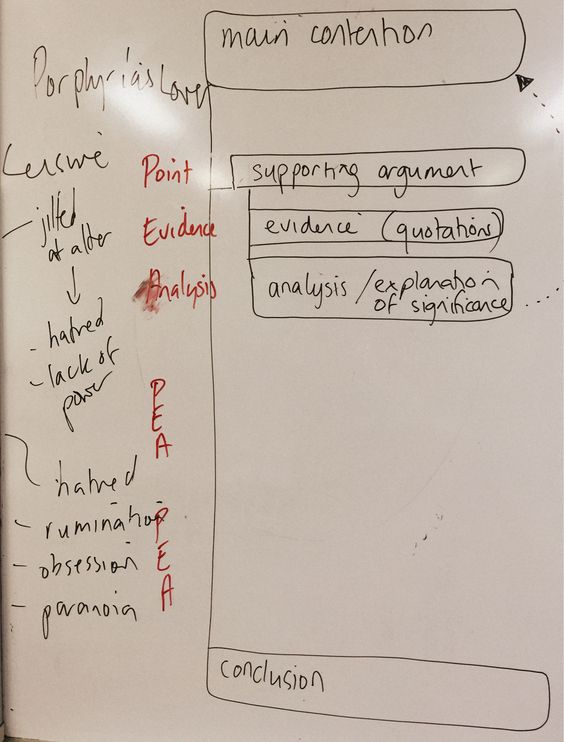

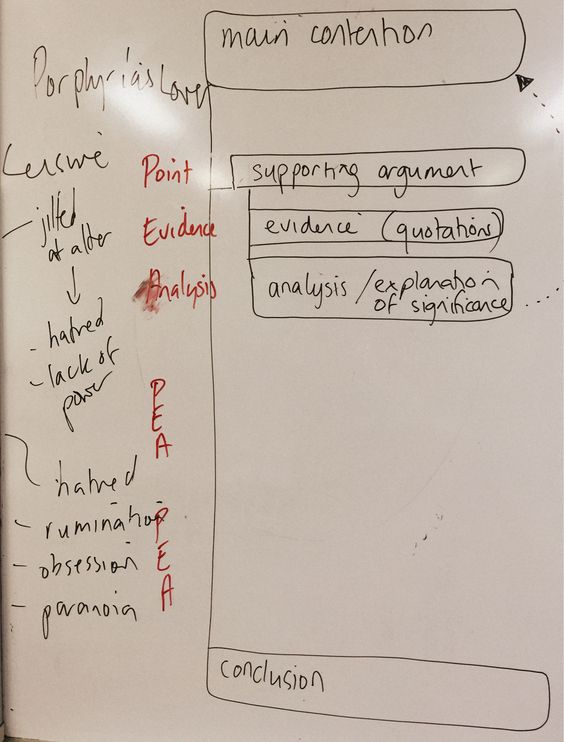

PORPHYRIA’S LOVER by Robert Browning

The rain set early in tonight,

The sullen wind was soon awake,

It tore the elm-tops down for spite,

and did its worst to vex the lake:

I listened with heart fit to break.

When glided in Porphyria; straight

She shut the cold out and the storm,

And kneeled and made the cheerless grate

Blaze up, and all the cottage warm;

Which done, she rose, and from her form

Withdrew the dripping cloak and shawl,

And laid her soiled gloves by, untied

Her hat and let the damp hair fall,

And, last, she sat down by my side

And called me. When no voice replied,

She put my arm about her waist,

And made her smooth white shoulder bare,

And all her yellow hair displaced,

And, stooping, made my cheek lie there,

And spread, o’er all, her yellow hair,

Murmuring how she loved me–she

Too weak, for all her heart’s endeavor,

To set its struggling passion free

From pride, and vainer ties dissever,

And give herself to me forever.

But passion sometimes would prevail,

Nor could tonight’s gay feast restrain

A sudden thought of one so pale

For love of her, and all in vain:

So, she was come through wind and rain.

Be sure I looked up at her eyes

Happy and proud; at last I knew

Porphyria worshipped me: surprise

Made my heart swell, and still it grew

While I debated what to do.

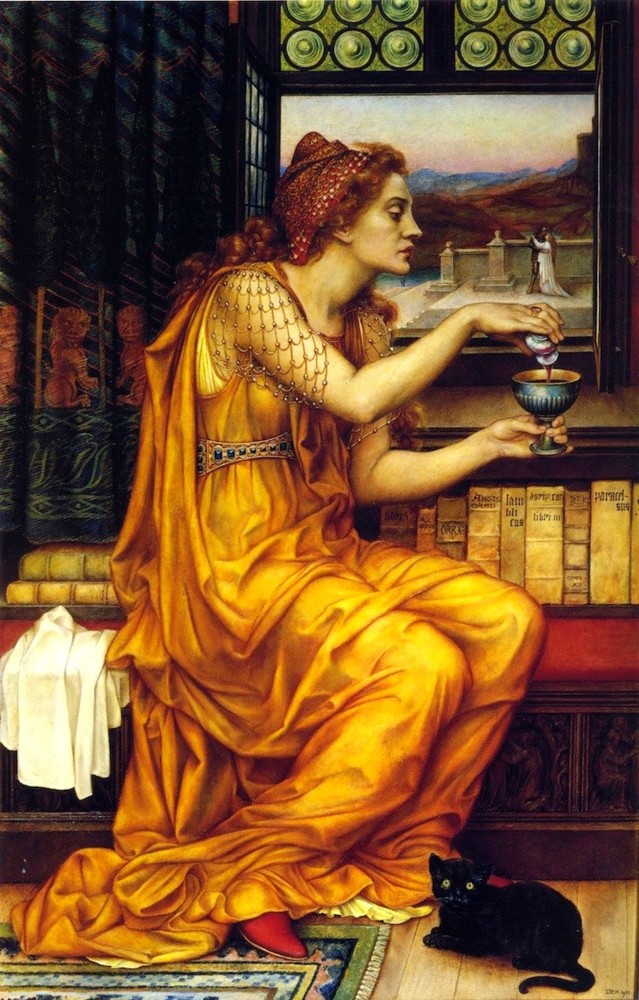

(Image source)

That moment she was mine, mine, fair,

Perfectly pure and good: I found

A thing to do, and all her hair

In one long yellow string I wound

Three times her little throat around,

And strangled her. No pain felt she;

I am quite sure she felt no pain.

As a shut bud that holds a bee,

I warily opened her lids: again

Laughed the blue eyes without a stain.

And I untightened next the tress

About her neck; her cheek once more

Blushed bright beneath my burning kiss:

I propped her head up as before

Only, this time my shoulder bore

Her head, which droops upon it still:

The smiling rosy little head,

So glad it has its utmost will,

That all it scorned at once is fled,

And I, its love, am gained instead!

Porphyria’s love: she guessed not how

Her darling one wish would be heard.

And thus we sit together now,

And all night long we have not stirred,

And yet God has not said a word!

About the poem –

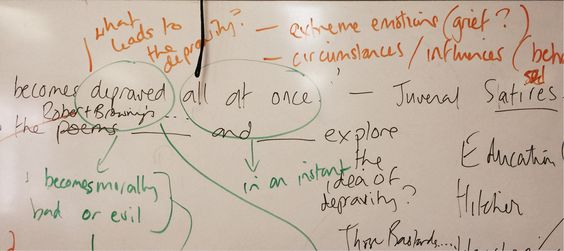

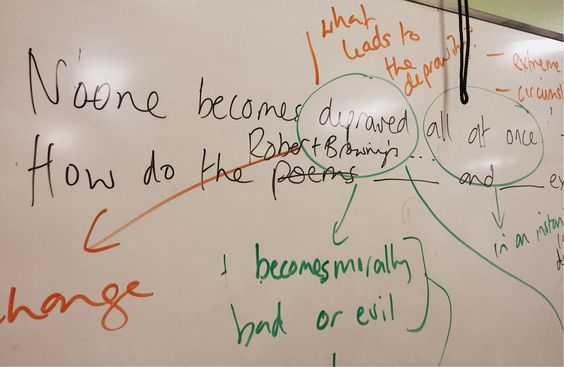

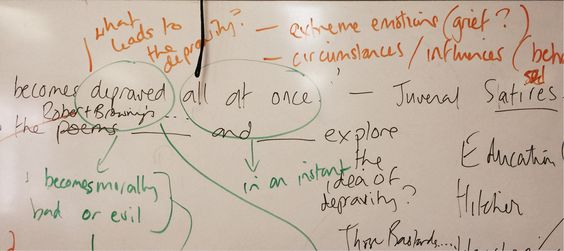

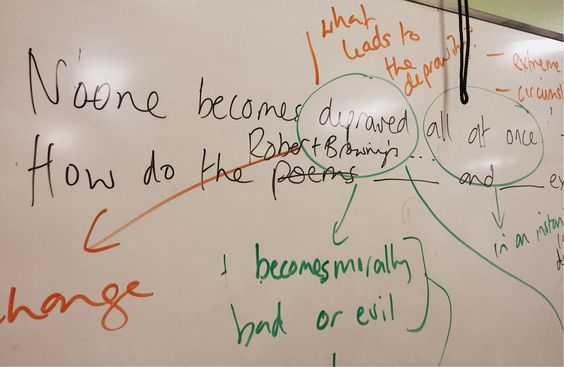

“Porphyria’s Lover” is one of the earliest of Robert Browning‘s dramatic monologues. The speaker of “Porphyria’s Lover” murders his girlfriend by strangling her with her hair, and then sits and admires the corpse for the rest of the night. The poem is from the point of view of a psychotic killer, which puts the reader in the uncomfortable position of reading the thoughts – or, if you’re reading the poem out loud, of giving voice to the thoughts – of a madman. This is just one reason that Browning’s monologues have received so much critical attention in recent decades.

Unfortunately for Robert Browning, though, most of his poetry was ignored during his life – his wife, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, was much more successful commercially. Ever heard of the sonnet “How do I love thee? Let me count the ways…“? That’s Elizabeth Barrett Browning, writing about her love for her husband, Robert. During the Victorian period (i.e., during the reign of Queen Victoria in Great Britain, or 1837-1901), readers preferred poems like Barrett Browning’s – poems about love and beauty – rather than poems like Robert Browning’s, which probe the psychological depths of criminals and murderers. (Source: Shmoop)

In the Victorian Era, the standard hairstyle for middle and upper-class women was an up-do because hair was considered a symbol of women’s sexuality, and that being so, hair was only worn loose in private, which was considered proper.

About Robert Browning –

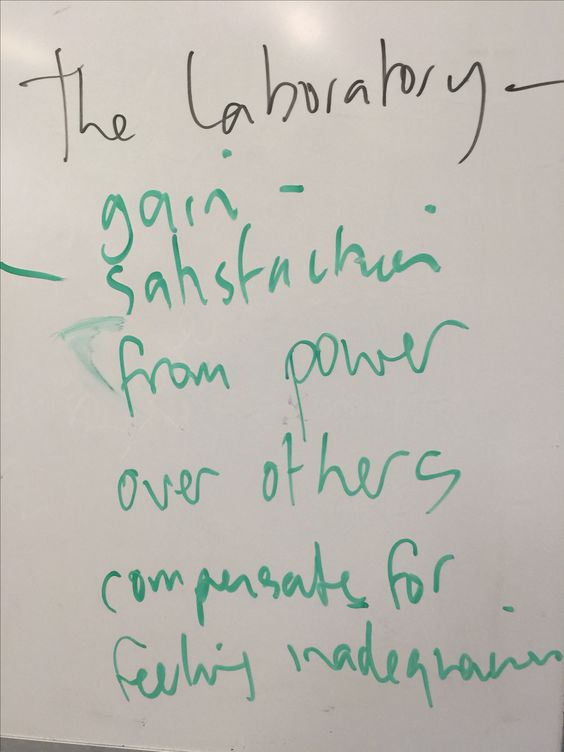

Browning was ultimately an optimist who believed that human love was the surest evidence of divine love and that knowledge of God could only be arrived at by intuition. Most of the poetry for which Browning is known today, however, is populated by villains whose inner lives are laid bare by Browning’s astute psychological insights; they are often people in whom love is missing. His villains are complex and interesting because they are victims of their uncontrolled desires, rather than embodiments of abstract vices.(Encyclopedia of British Writers, 1800 to the Present, Second Edition.)

Robert Browning was born on May 7, 1812, in Camberwell, England. His mother was an accomplished pianist and a devout evangelical Christian. His father, who worked as a bank clerk, was also an artist, scholar, antiquarian, and collector of books and pictures. His rare book collection of more than 6,000 volumes included works in Greek, Hebrew, Latin, French, Italian, and Spanish. Much of Browning’s education came from his well-read father. It is believed that he was already proficient at reading and writing by the age of five. A bright and anxious student, Browning learned Latin, Greek, and French by the time he was fourteen. From fourteen to sixteen he was educated at home, attended to by various tutors in music, drawing, dancing, and horsemanship. At the age of twelve he wrote a volume of Byronic verse entitledIncondita, which his parents attempted, unsuccessfully, to have published. In 1825, a cousin gave Browning a collection of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poetry; Browning was so taken with the book that he asked for the rest of Shelley’s works for his thirteenth birthday, and declared himself a vegetarian and an atheist in emulation of the poet. Despite this early passion, he apparently wrote no poems between the ages of thirteen and twenty. In 1828, Browning enrolled at the University of London, but he soon left, anxious to read and learn at his own pace. The random nature of his education later surfaced in his writing, leading to criticism of his poems’ obscurities. (Source: Poets.org)

Set in the modern society, and made contemporary Salome is a poem about a drunken woman who decapitates the heads of the men that she sleeps with.

This can be inferred from the title ‘salome’. Salome was a biblical character who turned insane after asking for a head on a platter from her step-father, the king. This historical context can help with the inference of the title and what the poem is about.

There are a references to biblical features throughout the poem ‘lamb turned to the slaughter’ (dehumanisation, of a sacrificial lamb)

The parable of the sheep and the goat. The sheep go to heaven and the goats go to hell. (Source)

I’d done it before

(and doubtless I’ll do it again,

sooner or later) woke up with a head on the pillow beside me – whose? –

what did it matter?

Good-looking, of course, dark hair, rather matted;

the reddish beard several shades lighter;

with very deep lines around the eyes,

from pain, Id guess, maybe laughter;

and a beautiful crimson mouth that obviously knew

how to flatter …

which I kissed …

Colder than pewter.

Strange. What was his name? Peter?

Simon? Andrew? John? I knew I’d feel better

for tea, dry toast, no butter,

so rang for the maid.

And, indeed, her innocent clatter

of cups and plates,

her clearing of clutter,

her regional patter,

were just what needed –

hungover and wrecked as I was from a night on the batter.

Never again!

I needed to clean up my act,

get fitter,

cut out the booze and the fags and the sex.

Yes. And as for the latter,

it was time to turf out the blighter,

the beater or biter,

who’d come like a lamb to the slaughter

to Salome’s bed.

In the mirror, I saw my eyes glitter.

I flung back the sticky red sheets,

and there, like I said – and ain’t life a bitch –

was his head on a platter.

About Carol Ann Duffy

“ Poetry, above all, is a series of intense moments – its power is not in narrative. I’m not dealing with facts, I’m dealing with emotion.” Carol Ann Duffy

The first female, Scottish Poet Laureate in the role’s 400 year history, Carol Ann Duffy’s combination of tenderness and toughness, humour and lyricism, unconventional attitudes and conventional forms, has won her a very wide audience of readers and listeners.

Watch an interview with Carol Ann Duffy.

About Salome:

Salome (/səˈloʊmiː/;[1] Greek: Σαλώμη Salōmē, pronounced [salóːmeː]; c. AD 14 – between 62 and 71) was the daughter of Herod II and Herodias. She is infamous for demanding and receiving the head of John the Baptist, according to the New Testament.

Salome is often identified with the dancing woman from the New Testament (Mark 6:17-29 and Matthew 14:3-11, where, however, her name is not given). Christian traditions depict her as an icon of dangerous female seductiveness, notably in regard to the dance mentioned in the New Testament, which is thought to have had an erotic element to it, and in some later transformations it has further been iconized as the Dance of the Seven Veils. Other elements of Christian tradition concentrate on her lighthearted and cold foolishness that, according to the gospels, led to John the Baptist‘s death. (Mark 6:25-27; Matthew 14:8-11)

A similar motif was struck by Oscar Wilde in his Salome, in which she plays the role of femme fatale. This parallel representation of the Christian iconography, made even more memorable by Richard Strauss’ opera based on Wilde’s work, is as consistent with Josephus’ account as the traditional Christian depiction; however, according to the Romanized Jewish historian, Salome lived long enough to marry twice and raise several children. Few literary accounts elaborate the biographical data given by Josephus.

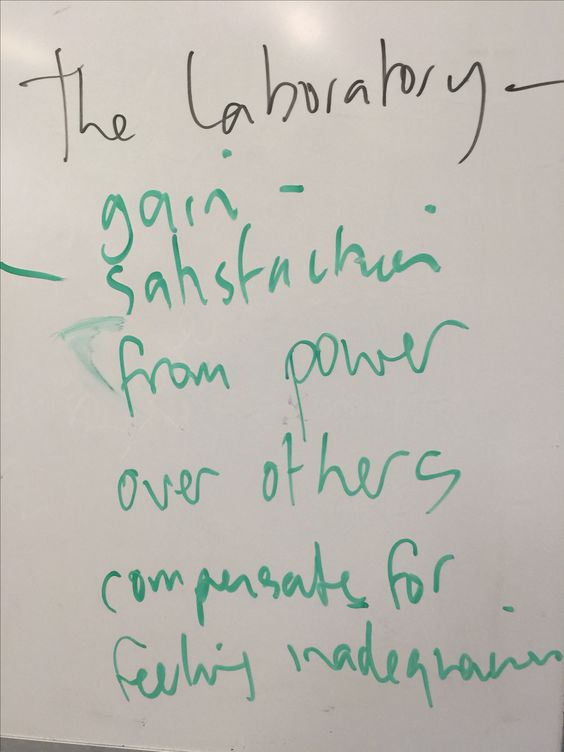

THE LABORATORY

NOW that I, tying thy glass mask tightly,

May gaze thro’ these faint smokes curling whitely,

As thou pliest thy trade in this devil’s-smithy–

Which is the poison to poison her, prithee?

He is with her; and they know that I know

Where they are, what they do: they believe my tears flow

While they laugh, laugh at me, at me fled to the drear

Empty church, to pray God in, for them! — I am here.

Grind away, moisten and mash up thy paste,

Pound at thy powder, — I am not in haste!

Better sit thus, and observe thy strange things,

Than go where men wait me and dance at the King’s.

That in the mortar — you call it a gum?

Ah, the brave tree whence such gold oozings come!

And yonder soft phial, the exquisite blue,

Sure to taste sweetly, — is that poison too?

Had I but all of them, thee and thy treasures,

What a wild crowd of invisible pleasures!

To carry pure death in an earring, a casket,

A signet, a fan-mount, a filligree-basket!

Soon, at the King’s, a mere lozenge to give

And Pauline should have just thirty minutes to live!

But to light a pastille, and Elise, with her head

And her breast and her arms and her hands, should drop dead!

Quick — is it finished? The colour’s too grim!

Why not soft like the phial’s, enticing and dim?

Let it brighten her drink, let her turn it and stir,

And try it and taste, ere she fix and prefer!

What a drop! She’s not little, no minion like me–

That’s why she ensnared him: this never will free

The soul from those masculine eyes, — say, ‘no!’

To that pulse’s magnificent come-and-go.

For only last night, as they whispered, I brought

My own eyes to bear on her so, that I thought

Could I keep them one half minute fixed, she would fall,

Shrivelled; she fell not; yet this does it all!

Not that I bid you spare her the pain!

Let death be felt and the proof remain;

Brand, burn up, bite into its grace–

He is sure to remember her dying face!

Is it done? Take my mask off! Nay, be not morose

It kills her, and this prevents seeing it close:

The delicate droplet, my whole fortune’s fee–

If it hurts her, beside, can it ever hurt me?

Now, take all my jewels, gorge gold to your fill,

You may kiss me, old man, on my mouth if you will!

But brush this dust off me, lest horror it brings

Ere I know it — next moment I dance at the King’s!

In a nutshell –

Sometimes the old stories are the best ones: Boy meets girl, boy dumps girl for another girl, first girl plots to murder second girl in an agonizingly slow and painful, way. Uh-oh. Okay, so maybe this isn’t just any old story. In spite of its innocent sounding title, Robert Browning’s “The Laboratory” tells the tale of one lady’s nasty plot to kill her romantic rival.

Robert Browning based his poem on a real-life figure, a French woman named Madame de Brinvilliers, a notorious serial killer who had her head chopped off in the seventeenth century. Her story is super-creepy, but also kind of fascinating—we can definitely see why Browning based a poem on her. (Source: Shmoop)

About Robert Browning

Although the early part of Robert Browning’s creative life was spent in comparative obscurity, he has come to be regarded as one of the most important poets of the Victorian period. His dramatic monologues and the psycho-historical epic The Ring and the Book (1868-1869), a novel in verse, have established him as a major figure in the history of English poetry. Read more about Robert Browning.

EDUCATION FOR LEISURE

Today I am going to kill something. Anything.

I have had enough of being ignored and today

I am going to play God. It is an ordinary day

A sort of grey with boredom stirring in the streets

I squash a fly against the window with my thumb.

We did that at school. Shakespeare. It was in

another language and now the fly is in another language.

I breathe out talent on the glass to write my name.

I am a genius. I could be anything at all, with half

the chance. But today I am going to change the world.

Something’s world. The cat avoids me. The cat

knows I am a genius, and has hidden itself.

I pour the goldfish down the bog. I pull the chain.

I see that it is good. The budgie is panicking.

Once a fortnight, I walk the two miles into town

for signing on. They don’t appreciate my autograph.

There is nothing left to kill. I dial the radio

and tell the man he’s talking to a superstar.

He cuts me off. I get our bread-knife and go out.

The pavements glitter suddenly. I touch your arm.

By Carol Ann Duffy

Beloved sweetheart bastard. Not a day since then

I haven’t wished him dead. Prayed for it

so hard I’ve dark green pebbles for eyes,

ropes on the back of my hands I could strangle with.

Spinster. I stink and remember. Whole days

in bed cawing Nooooo at the wall; the dress

yellowing, trembling if I open the wardrobe;

the slewed mirror, full-length, her, myself, who did this

to me? Puce curses that are sounds not words.

Some nights better, the lost body over me,

my fluent tongue in its mouth in its ear

then down till I suddenly bite awake. Love’s

hate behind a white veil; a red balloon bursting

in my face. Bang. I stabbed at a wedding-cake.

Give me a male corpse for a long slow honeymoon.

Don’t think it’s only the heart that b-b-b-breaks.

Carol Ann Duffy

My Last Duchess

That’s my last Duchess painted on the wall,

Looking as if she were alive. I call

That piece a wonder, now: Frà Pandolf’s hands

Worked busily a day, and there she stands.

Will ‘t please you sit and look at her? I said

“Frà Pandolf” by design, for never read

Strangers like you that pictured countenance,

The depth and passion of its earnest glance,

But to myself they turned (since none puts by

The curtain I have drawn for you, but I)

And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst,

How such a glance came there; so, not the first

Are you to turn and ask thus. Sir, ’twas not

Her husband’s presence only, called that spot

Of joy into the Duchess’ cheek: perhaps

Frà Pandolf chanced to say, “Her mantle laps

Over my Lady’s wrist too much,” or “Paint

Must never hope to reproduce the faint

Half-flush that dies along her throat”; such stuff

Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough

For calling up that spot of joy. She had

A heart… how shall I say?… too soon made glad,

Too easily impressed; she liked whate’er

She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.

Photo source

Sir, ’twas all one! My favour at her breast,

The dropping of the daylight in the West,

The bough of cherries some officious fool

Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule

She rode with round the terrace — all and each

Would draw from her alike the approving speech,

Or blush, at least. She thanked men, — good; but thanked

Somehow… I know not how… as if she ranked

My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name

With anybody’s gift. Who’d stoop to blame

This sort of trifling? Even had you skill

In speech — (which I have not) — to make your will

Quite clear to such an one, and say, “Just this

Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss,

Or there exceed the mark” — and if she let

Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set

Her wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse,

— E’en then would be some stooping; and I chuse

Never to stoop. Oh, sir, she smiled, no doubt,

Whene’er I passed her; but who passed without

Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands;

Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands

As if alive. Will ‘t please you rise? We’ll meet

The company below, then. I repeat,

The Count your Master’s known munificence

Is ample warrant that no just pretence

Of mine for dowry will be disallowed;

Though his fair daughter’s self, as I avowed

At starting, is my object. Nay, we’ll go

Together down, Sir! Notice Neptune, though,

Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity,

Which Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me.

About the poem

Browning’s inspiration for “My Last Duchess” was the history of a Renaissance duke, Alfonso II of Ferrara, whose young wife Lucrezia died in suspicious circumstances in 1561. Lucrezia was a Medici – part of a family that was becoming one of the most powerful and wealthy in Europe at the time. During Lucrezia’s lifetime, however, the Medici were just beginning to build their power base and were still considered upstarts by the other nobility. Lucrezia herself never got to enjoy riches and status; she was married at 14 and dead by 17. After her death, Alfonso courted (and eventually married) the niece of the Count of Tyrol.

Robert Browning takes this brief anecdote out of the history books and turns it into an opportunity for readers to peek inside the head of a psychopath. Although Browning hints at the real-life Renaissance back-story by putting the word “Ferrara” under the title of the poem as an epigraph, he removes the situation from most of its historical details. It’s important to notice that the Duke, his previous wife, and the woman he’s courting aren’t named in the poem at all. Even though there were historical events that inspired the poem, the text itself has a more generalized, universal, nameless feel. (Source)

About Robert Browning

Robert Browning (1812-1889) was heavily influenced as a youngster by his father’s extensive collection of books and art. His father was a bank clerk and collected thousands of books, some of which were hundreds of years old and written in languages such as Greek and Hebrew. By the time he was five, it was said that Browning could already read and write well. He was a big fan of the poet Shelley and asked for all of Shelley’s works for his thirteenth birthday. By the age of fourteen, he’d learned Latin, Greek and French. Browning went to the University of London but left because it didn’t suit him.

He married fellow poet Elizabeth Barrett but they had to run away and marry in secret because of her over-protective father. They moved to Italy and had a son, Robert. Father and son moved to London when Elizabeth died in 1861.

Browning is best known for his use of the dramatic monologue. My Last Duchess is an example of this and it also reflects Browning’s love of history and European culture as the story is based on the life of an Italian Duke from the sixteenth century. (Source)

Hitcher

I’d been tired, under

the weather, but the ansaphone kept screaming.

One more sick-note. mister, and you’re finished. Fired.

I thumbed a lift to where the car was parked.

A Vauxhall Astra. It was hired.

I picked him up in Leeds.

He was following the sun to west from east

with just a toothbrush and the good earth for a bed. The truth,

he said, was blowin’ in the wind,

or round the next bend.

(This references the folk-rock singer-songwriter Bob Dylan, perhaps one of the most influential poet of the 20th century. The first of Dylan’s songs to really bring him to public attention was “Blowin’ In The Wind”, a #2 hit for Peter, Paul and Mary.)

I let him have it

on the top road out of Harrogate -once

with the head, then six times with the krooklok

in the face -and didn’t even swerve.

I dropped it into third

and leant across

to let him out, and saw him in the mirror

bouncing off the kerb, then disappearing down the verge.

We were the same age, give or take a week.

He’d said he liked the breeze

to run its fingers

through his hair. It was twelve noon.

The outlook for the day was moderate to fair.

Stitch that, I remember thinking,

you can walk from there.

Photo source: The Poetry Society

About Simon Armitage

Simon Armitage was born in West Yorkshire, England in 1963. He earned a BA from Portsmouth University in geography, and an MS in social work from Manchester University, where he studied the impact of televised violence on young offenders. He worked as a probation officer for six years before focusing on poetry. In 2015, he was elected Oxford Professor of Poetry.

Known for his deadpan delivery, Armitage’s formally assured, often darkly comic poetry is influenced by the work of Ted Hughes, W.H. Auden, and Philip Larkin. As a reviewer for the PoetryArchive.org observed, “With his acute eye for modern life, Armitage is an updated version of Wordsworth’s ‘man talking to men.’” Read the rest here.

Photo source: Udo Schroter on Flickr

Those Bastards In Their Mansions by Simon Armitage

Those bastards in their mansions:

to hear them shriek, you’d think

I’d poisoned the dogs and vaulted the ditches,

crossed the lawns in stocking feet and threadbare britches,

forced the door of one of the porches, and lifted

the gift of fire from the burning torches,

then given heat and light to streets and houses,

told the people how to ditch their cuffs and shackles,

armed them with the iron from their wrists and ankles.

Those lords and ladies in their palaces and castles,

they’d have me sniffed out by their beagles,

picked at by their eagles, pinned down, grilled

beneath the sun,

Me, I stick to the shadows, carry a gun.

About Simon Armitage

Simon Armitage was born in Huddersfield, a large town in West Yorkshire, England, on May 26, 1963. His first poetry collection, Zoom! (1989), earned him a place among the new generation of poets with its fresh mix of street smarts, stand-up comedy, pub talk, and serious social critique. Armitage would continue to make good use of his years in social work in later collections. His poetry examines contemporary characters and scenes with the eye of a social historian and often climaxes in seriocomic moments, as in “Poem,” one of his most famous pieces: “And every week he tipped up half his wage / And what he didn’t spend each week he saved. / And praised his wife for every meal she made. / And once, for laughing, punched her in the face.” As with many of his peers, he adapts more traditional rhythms and forms to his subject, largely eschewing formal experimentation.

In addition to his poetry, Armitage is known for his plays, television work, and prose.Recently, he has published two novels, Little Green Man in 2001 and The White Stuff in 2004, that explore the darker side of thirtysomething life in the United Kingdom. (Encyclopedia of British Writers, 1800 to the Present, Second Edition.)

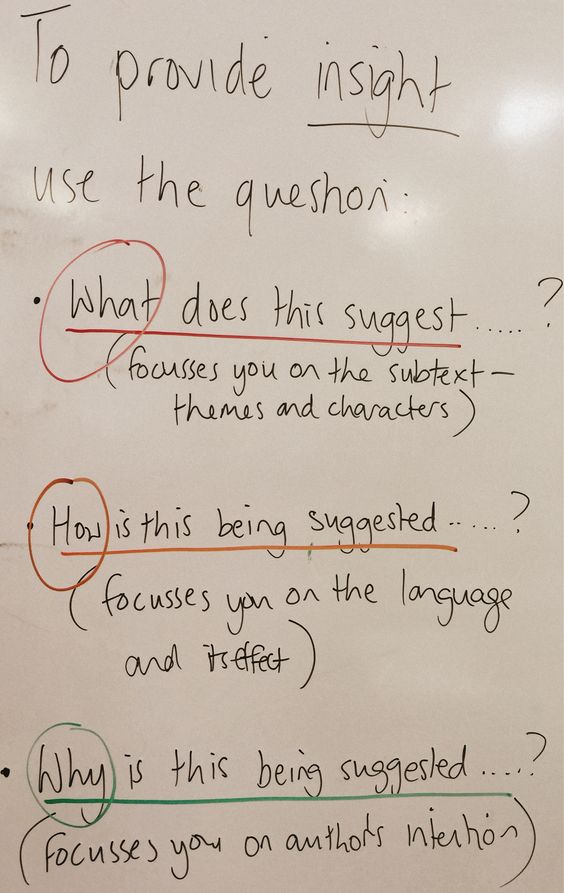

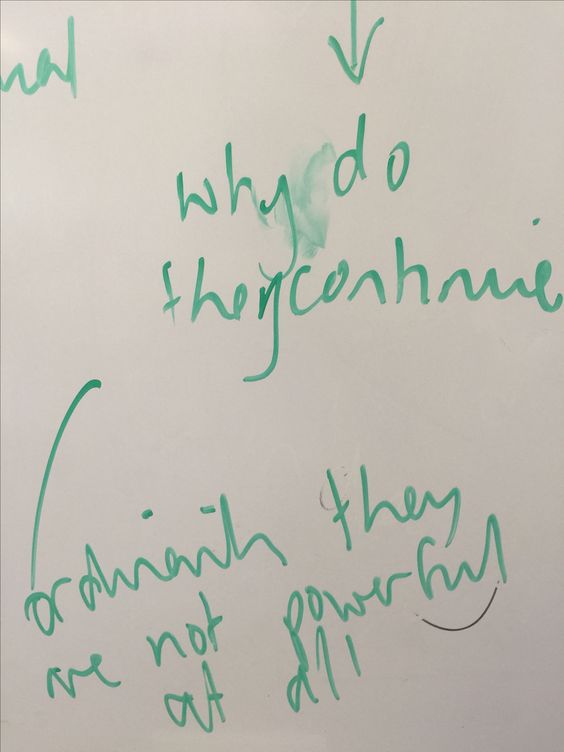

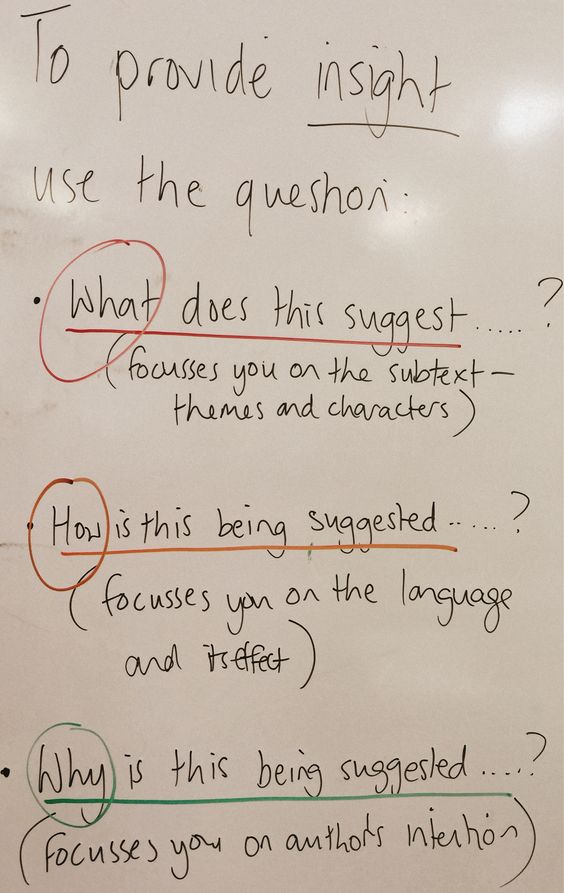

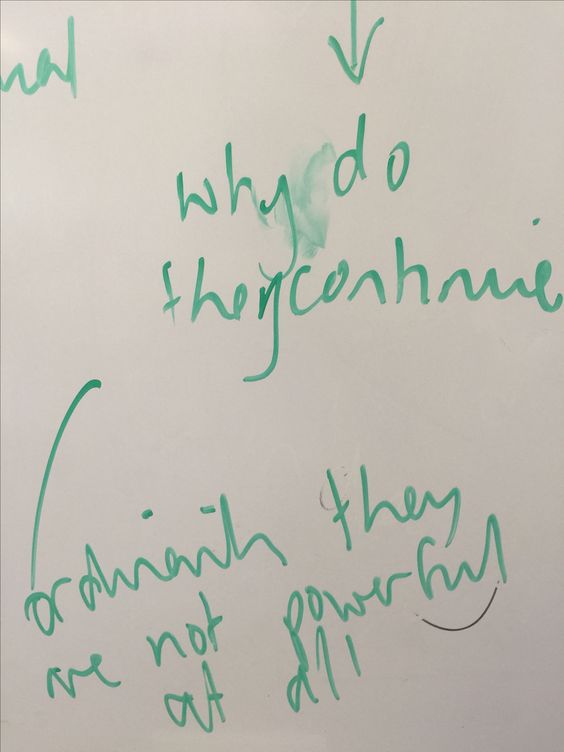

What is the difference between the idea of an essay and an essay of ideas?

It’s often tempting to begin an essay with this question in mind: ‘What do I (read: my teacher) want my essay to sound like?’ If you answer this question with , ‘Like an essay,’ then chances are you are going to use vocabulary and phrases which you can string together to make your essay sound like an essay. Essayspeak. Worse still, you might answer this question with: ‘Like I know what I’m talking about when actually I’m not at all sure.’ This is going to be a very mysterious read for anyone seeking knowledge and understanding of the thing about which your are writing.

These students are focusing more on sounding like an essay rather than presenting their knowledge or understanding:

The main idea that the poem seems to revolve around is a very important one…

The poem is one that describes an old man in relation to his surroundings in a very imaginative way….

Plath uses this technique as many readers can relate to this. She does this extremely well and it helps her get her point across to the reader.

So, what if you being with the question: ‘What do I know or understand and how can I show this in my essay?’ Notice the focus here. Assume we can all communicate our ideas in writing (the ‘essay’ bit of the task), and instead the focus is on what we know or understand about the subject matter of the essay. Guess what? An essay is simply sharing your knowledge and understanding with others in writing. So the focus should not be about appearing to write an essay but rather the knowledge and understanding that is being communicated by it’s very nature is an essay. The quality of the student’s thinking is the focus; how that gets written up is secondary to the content.

Remember that an essay is your big ideas about others’ big ideas and how they are presented.

In short:

ACTIVITY