Take a photo of your class quickly using an ipad camera. The image will most likely have some problems: not everyone will be in the frame; not everyone will be in focus. Take a second photo of the class and take the time for the ipad camera to find its focus and for you to ensure that all students are in the frame. The resulting photograph will undoubtedly be better. You will be able to zoom in on the detail of a student’s facial expression to interpret their mood from their expression, or zoom out to interpret the mood of the class as a whole.

Now take this theory (which involves giving time to the subject matter and the skill) and apply it to unseen poetry analysis.

Focus: You need to know what the poem is about or what happens in it. This is the subject matter of the poem – the bit that you need to lock onto and get an idea of. Extract these details (make some notes) and have a think about them as you re-read the poem. Sometimes taking them out of the poem and making a little list will enable you to make connections between them more easily than searching for them each time in the poem as you read through it.

Frame: Make sure you have the whole poem in your sights. Your analysis should have breadth. Ignoring parts of the poem because they don’t immediately make sense is an unwise decision. It is more than likely these parts hold the key to unlocking some of the complexity of the poem and the poet’s message. Think back to poems we have done in class: they often begin with the easier, concrete details and move into figurative language which deals with more abstract, complex ideas.

Zoom in: this is what you do when you look at the little details in a poem; turns of phrase; word choices; similes, metaphors, personification, repetition, sibilance, alliteration, assonance, ellipsis, end-stopped lines, caesura, enjambement, rhyme, rhythm (the list goes on). You job is not to ‘spot the device’; your job is to take a closer look at the language and explain its intended effect. We zoom in to find evidence to support our interpretation of a poem. Once you have these quotations, use these questions to get to word-level analysis:

- What does this suggest?

- What does the speaker (or writer) think or feel about this?

- what does the author want us to think or feel about this?

- Are there any other instances in the poem that link to this idea?

Zoom out: this is what you do when you try to identify the ‘big ideas‘ in a poem. These could be things like beauty, identity, loneliness, love, power, relationships (between whom?), one’s past, one’s sense of self, evil, honesty etc. There are so many you couldn’t imagine them all. Reading the poem, you should get a feel for the ‘big idea/s’. Re-read the poem and look for clues to support your theory. The clues to these big abstract things are in the concrete details in the poem. To zoom even further out, you need to get to this big question:

What is the author suggesting about [the big idea] and what this suggests about what it means to be human? Yes, it’s a wide zoom out but you’re only going this far because you have all the evidence there in the detailed zoom in.

So the secret is to READ. Relax and RE-READ. This is where diffuse thinking is important. Your first idea or theory (‘it’s all about cancer’) may not have enough evidence to be supported. You need to be open to variations on a theme. The poem may well be about adversity, relationships and facing the idea of death but these themes could feature in a poem about exams as much as one about illness. You don’t have to come up with a concrete answer or harebrained theory.

Test your thinking by re-reading the text.

Take the time for the poem to come into focus. You won’t be able to do this kind of thorough thinking about each of the three poems you have to choose from in the exam, so make a decision in reading time and choose the one that seems clearest to you. Use your WIG:WIDGY ratio to determine the one which you ‘get’ the most.

How does this look when you start thinking about a poem? Read Gerald Manley Hopkins’s poem God’s Grandeur and then look at the notes I have made on the focus and frame sheet which helps me to remember the zoom in (little details) and the zoom out (big ideas) of the analytical thought process.

God’s Grandeur in the frame

Then, the question is how to write this top-class thinking up?

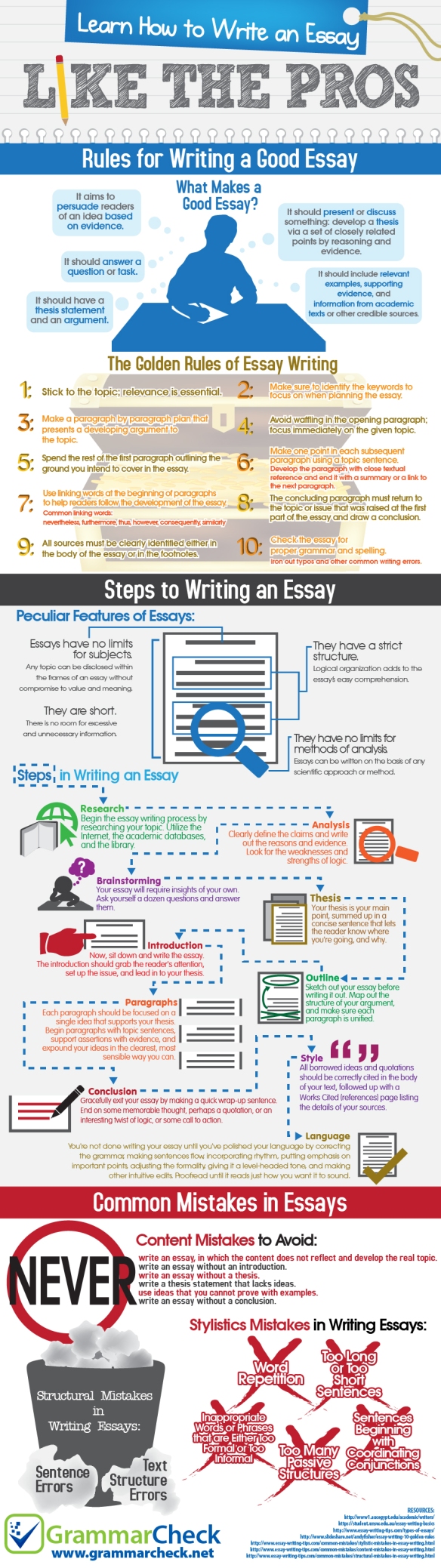

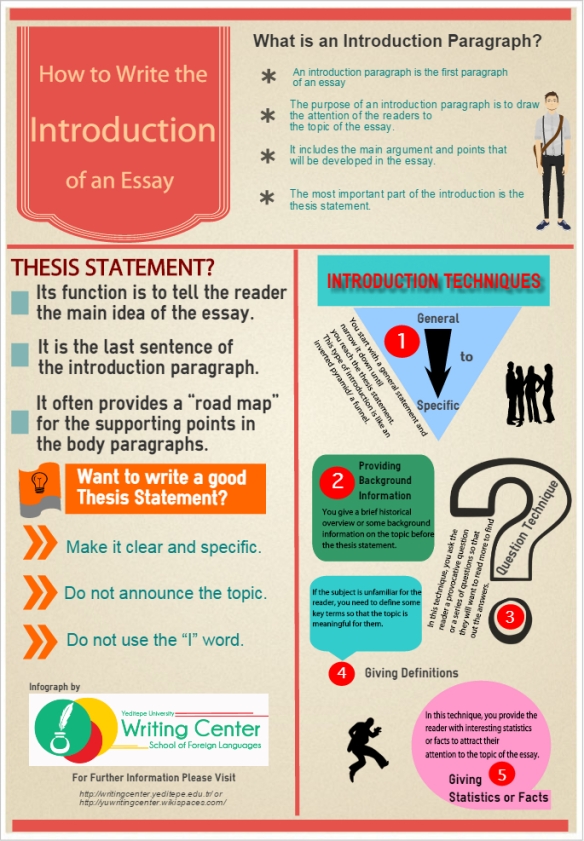

You will use a traditional text essay structure and write in a formal register. No-one wants to hear an account of how you felt when you were reading the poem (none of this kind of unedifying drivel: “At first I thought this but then I thought that.” Save it for your diary, kiddo.) Instead you will have an introduction, body paragraphs and a conclusion. You will write in the present tense; despite the fact that you poet may be deceased, he or she lives on in the poem they have written.

INTRODUCTION:

Remember that this is the ‘sucker punch‘ of your essay. It knocks out the examiner with its insight and clarity. The examiner should be left a little breathless, if you will. It’s show-what-you-know time before you step them through how you got there. This is no time for treading-water-while-I-think writing which shows zero understanding of the poem in question (e.g.”There are lots of different themes in this poem and using many different poetic devices the poet presents a powerful message.” Garbage.) This is also no time for withholding information like a whodunnit novel or for teasing the examiner with an elaborate dance of the seven veils. This is sucker punch time: OOF!

An introduction should signpost:

- the poem and poet

- the focus of the poem

- the poet’s message (your big idea about their big idea/s)

- the speaker of the poem’s views and values (explaining the big idea might get you here)

BODY PARAGRAPHS:

Use your common sense here and take your cues from the poem and its subject matter. Your body paragraphs can follow:

- the poem’s ‘big ideas’

- the stages (or stanzas) of the poem

- the poem’s focus (subject matter) and how we are positioned to view it

A body paragraph should:

- have a strong topic sentence which shows understanding of the poem/poet’s purpose and message (your big idea about their big idea)

- present evidence (quotations) of the way the audience is positioned to view these things

- draw our attention to the complexity of the poem: its use of technique or its presentation of an idea

- make observations of the language and structure

- link structure and language to the way an idea is being presented and how that links to the ideas presented in the poem as a whole

- draw connections across the text: compare and contrast and connect

- draw connections between the focus of the poem, the big ideas and the little details

- provide a nuanced interpretation. Avoid the oversimplification of the poem-in-a-nutshell approach:

e.g. ‘This poem is all about love.’ [Mic drop]

Instead, look closely at the ideas presented and show a refinement of understanding:

e.g. ‘This poem is a celebration of the precious nature of love between siblings and at the same time a warning of how the loss of a parent can compromise that bond.’

- get the poetic devices terminology right (don’t misuse a term)

- avoid praise and criticism (this is really about ascertaining what the poem/poet sets out to do, not how well they do it)

- avoid personal journey language or vague expressions that tell the reader nothing of your understanding (“I really liked this – it makes the poem flow better and provides a deeper understanding”)

CONCLUSION:

You should come back to the poem’s message in light of the evidence you have presented. You can look at the big picture here too – what the poem suggests about [the big idea] and what it means to be human.